What global shipbuilding data from 2014–2024 demands of Indian policymakers and industry leaders

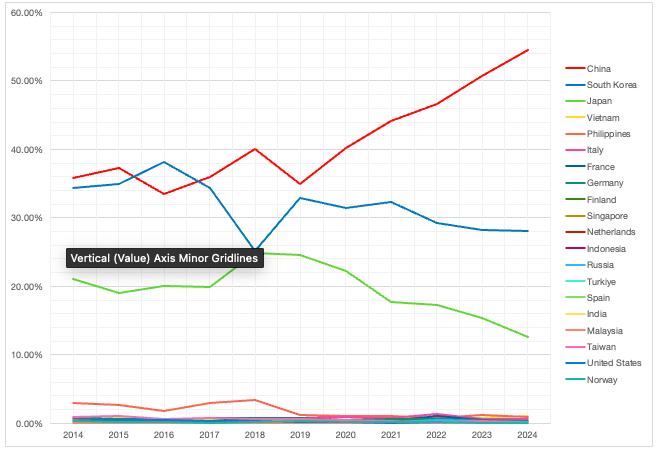

Shipbuilding is treated as a strategic industry in East Asia and Europe because it shapes trade competitiveness, energy transition, maritime security, and long-term industrial capability. An examination of country-wise shipbuilding output from 2014 to 2024 [1] shows that this industry has become one of the most highly concentrated in the world, dominated by a handful of Asian nations. For India, the central question is stark: can it still make a meaningful impact in global shipbuilding, or has that window already narrowed beyond reach.

1. Global shipbuilding: consolidation, not globalisation

Figure 1: Global shipbuilding market share by top three countries, 2014 vs 2024

From 2014 to 2024, shipbuilding moved against the broader trend of diversification in global manufacturing. In 2014, China, South Korea, and Japan together accounted for roughly 91% of global shipbuilding output; by 2024 their combined share was close to 95%, an extraordinary level of concentration for a core industrial sector. This reinforces that shipbuilding is no longer a purely market‑led activity but a policy‑shaped, capital‑intensive and scale‑driven industry where late entry is structurally difficult.

China’s trajectory is the defining feature of this decade. Its global share rises from about 36% in 2014 to more than 54% by 2024, meaning Chinese yards now deliver more tonnage than the rest of the world combined. South Korea and Japan retain strong positions but show gradual erosion or stagnation, highlighting the intense pressure even on legacy leaders.

2. China, Korea, Japan: three distinct strategies

China’s dominance is not driven by labour costs alone. Over two decades it has aligned industrial policy, state-backed finance, domestic shipping demand, yard modernisation and an integrated marine supply chain around shipbuilding. Shipyards are treated as strategic infrastructure, supported by long-tenure finance and export credit that reduce risk for global buyers and enable aggressive capacity and technology investments. [2]

South Korea has deliberately repositioned itself towards high‑value segments such as LNG carriers, very large crude carriers, and ultra‑large container ships. While its overall share declines from a peak of about 38% in 2016 to around 28% in 2024, it dominates technologically complex vessels with higher margins and technological spillovers. Japan, by contrast, has seen its share fall from around 21% to 12.6% over the same period, reflecting structural headwinds including an ageing workforce, slower yard modernisation and cost pressures.[3]

The strategic message for India is clear: even incumbents must keep reinventing their positioning; inaction or complacency inevitably leads to loss of share.

3. The long tail—and India’s place in it

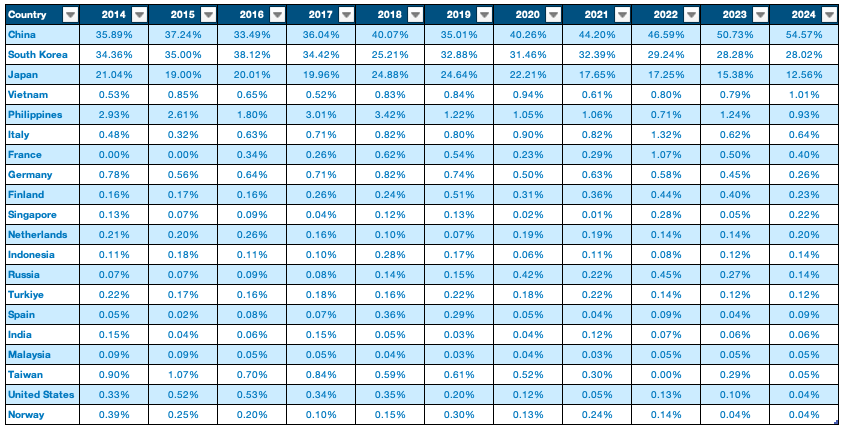

Figure 2: Market share of “long‑tail” shipbuilding countries, 2014 vs 2024

Outside the top three, no country consistently exceeds about 2% of global shipbuilding output. European countries survive by specialising in high‑complexity niches such as cruise ships, naval vessels, research ships and offshore wind service vessels, while the United States has largely exited commercial shipbuilding in favour of naval programmes and Jones Act–protected domestic routes.

India’s performance over this period is sobering. Its global share oscillates between roughly 0.03% and 0.15%, with no sustained upward trend, despite a long coastline, growing domestic maritime demand and a substantial engineering talent pool. This pattern points to structural rather than cyclical weaknesses: India has not yet translated its geographic and human‑capital advantages into scale, technology depth or stable order books.[4]

4. Why India underperforms: a structural diagnosis

| Dimension | Current reality in India | Benchmark in leading shipbuilding nations |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of capital | High interest rates, limited long-tenure finance for yards and buyers. [5] | Concessional, long-tenure credit with sovereign guarantees and strong export-credit agencies. [6] |

| Scale and yard size | Fragmented, with few large commercial yards and heavy dependence on defence work. | Mega‑yards with standardised designs, modular construction and global order books. [7] |

| Supply chain | Significant import dependence for engines, propulsion, electronics and specialised steel. [8] | Deep domestic supplier ecosystems, often clustered around shipbuilding hubs. [2] |

| Policy stability | Episodic schemes; improvements via Shipbuilding Financial Assistance Policy[ 9], but still modest compared with East Asia. | Multi‑decade, predictable support tied to national maritime strategies. |

| Technology & skills | Pockets of excellence; limited adoption of automation, digital twins and green-fuel design tools. | Continuous R&D investment and strong yard‑vendor linkages in advanced technologies. |

Table 1: Structural drivers of underperformance in Indian shipbuilding

Shipbuilding demands long-tenure, low-cost debt, predictable order pipelines, yard modernisation at scale, and stable regulatory and classification frameworks. India’s current ecosystem still forces many shipyards into project-to-project survival mode, discouraging technology upgrades and productivity-enhancing investments. Recent policies—including the Shipbuilding Financial Assistance Policy (SBFAP) and proposed enhancements focusing on green vessels—are positive but not yet transformative in size or duration.

5. Is a 10% global share plausible—and where should India play?

A target of 10% global shipbuilding share over the next two decades is ambitious but not implausible if framed correctly. India does not need to compete with China or South Korea across all blue‑water vessel categories; instead, it must secure leadership in specific, high‑potential segments. These should be segments where scale economies are moderate, system integration and local operating knowledge matter more, and domestic demand can anchor early growth.

Priority segments for India

- Inland and coastal cargo vessels, including bunkers and tankers, aligned with Sagarmala and inland waterways programmes.[10]

- Green propulsion platforms (electric, hybrid, LNG, hydrogen‑ready) for pilot projects that can be scaled to export markets.[11]

- Short‑sea and regional passenger vessels for island connectivity, coastal tourism and regional trade.[12]

- Workboats and service vessels for ports, offshore support and emerging offshore wind installations. (for MSME Yards)

- Electric and hybrid ferries for urban and regional passenger transport in coastal cities and riverine corridors. (for MSME Yards) [13]

These categories intersect with India’s broader goals on decarbonisation, coastal shipping, urban mobility and blue‑economy development, creating scope for integrated policy design rather than isolated schemes.

6. Policy shifts required: from projects to systems

Reaching a 10% share is not primarily a yard‑level challenge; it is a system‑design challenge that spans policy, finance, technology and demand.

- Treat shipbuilding as infrastructure, not discrete procurement

Public orders for ferries, patrol craft, tugs, coastal vessels and inland ships must be aggregated into long‑term, predictable pipelines rather than fragmented tenders. National and state governments can use coordinated procurement plans, with standardised designs, to provide volume visibility that justifies automation, training and cluster development in shipyards.[14] - Close the financing gap with patient, specialised capital

India needs a dedicated shipbuilding finance window—possibly Maritime Development Fund—that offers long-tenure loans, buyer’s credit and guarantees at internationally competitive rates. SBFAP and its green‑ship extensions should be given at least a 10–15 year horizon with clear budgetary commitments, ensuring that shipyards and financiers can plan beyond short policy cycles. - Build focused clusters and technology centres

Integrated coastal clusters that co‑locate shipyards, steel and fabrication units, component suppliers, design houses and testing facilities can sharply reduce costs and cycle times. A national Ship Technology Centre, linked with maritime universities and classification societies, should prioritise digital design, modular construction, and green propulsion, enabling Indian yards to leapfrog rather than follow slowly. - Use domestic demand to create exportable standards

Regulatory frameworks such as the Coastal Shipping Act and green‑vessel guidelines for inland waters can create standardised vessel types suitable for both domestic and export markets. If India can establish proven designs for electric ferries, green tugs or riverine passenger vessels at scale, it can credibly market these to other developing and emerging economies facing similar operating conditions.

7. A decade of data, a decades-long decision

The 2014–2024 data does not show that India “missed the bus”; it shows that India never boarded it properly. The next twenty years offer a different, more focused opportunity built around green, regional and specialised vessels rather than bulk ocean-going tonnage. With coordinated policy, patient finance and a clear choice of segments, India can move from the margins to a meaningful share of global shipbuilding, supporting its broader maritime and industrial ambitions.[15]

Shipbuilding is an industry that rewards countries willing to think in decades rather than budget cycles. India has the coastline, human capital and domestic demand; the outstanding question is whether it will now show the patience—and the intent—to treat shipbuilding as a core national capability instead of a peripheral opportunity.

Figure 3: Global shipbuilding market share by top twenty countries, 2014 vs 2024

References

[3] – https://think.ing.com/articles/asia-shipbuilding-renaissance/

[4] – https://www.pmfias.com/indias-shipbuilding-sector/

[6] – https://savearchive.zbw.eu/bitstream/11159/2601/1/1046207334.pdf

[7] – https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/ship-building-market

[9] – https://www.shipbuilding.nic.in

[10] – https://sagarmala.gov.in/projects/coastal-shipping-inland-waterways

[12] – https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2153799®=3&lang=2