My presentation given at Kochi Boat show on 28th January.

India’s waterways—rivers, lakes, backwaters, canals, and coastal routes—carry millions of passengers and tonnes of cargo every year. Yet, most of these operations still rely on diesel boats that are inefficient, polluting, noisy, and increasingly uneconomical. Electric and solar-electric boats offer a compelling alternative, not as a futuristic concept, but as a practical and scalable solution for Indian conditions.

The Problem with Diesel Boats

The challenges of diesel boats are well known but often underestimated. [1][2]

First, diesel boats contribute significantly to air and water pollution. Fuel leaks, exhaust emissions, and oil discharge directly affect fragile aquatic ecosystems.

Second, they generate noise, vibration, and fuel smell, reducing passenger comfort and making them unsuitable for tourism and ecologically sensitive areas.

Third, many existing passenger boats—especially monohull designs—operate with low stability margins, a problem that becomes severe during overloading and overcrowding. While this issue is not directly caused by diesel propulsion, it is endemic to the legacy fleet that dominates Indian waterways.

Finally, and most critically for operators, diesel boats suffer from high operating expenditure (OPEX). In many subsidised public transport systems, daily revenue often struggles to cover fuel costs alone, leaving little room for maintenance, crew, or capital recovery.

Why Electric Catamarans Change the Equation

Electric catamaran boats inherently eliminate all of these problems. They produce zero local emissions, operate quietly with minimal vibration, and provide a more comfortable passenger experience. Catamaran hulls also offer higher stability, addressing safety concerns common in overcrowded monohull vessels.

However, the real transformation begins not with electrification, but with good design.

Design as the First Step to Lower OPEX

Reducing operating cost starts with reducing the energy required to move the boat.

The first design intervention is weight reduction. By shifting from traditional materials such as steel and wood to GRP (glass-reinforced plastic) and, in select cases, aluminium, the structural weight of the vessel can be significantly reduced. This can be as low as 50% of traditional boat weight.

The second intervention is optimisation of the underwater hull form. Reducing hydrodynamic drag lowers the power required to achieve a given speed.

The combined effect of lighter structures and optimised hulls can reduce propulsion power requirements to nearly one-third of those of legacy boats.

Switching from Diesel to Electricity

Once power demand is minimised through design, the next step is changing the energy source.

With diesel priced around ₹90 per litre, the effective cost of producing one unit (kWh) of mechanical power from a diesel engine is approximately ₹35, after accounting for engine efficiency.[3]

In contrast, with grid electricity priced around ₹7 per kWh, the cost of producing one unit of mechanical power from an electric motor is roughly ₹10. This represents another threefold reduction in energy cost.[3]

Solar: The Third Lever

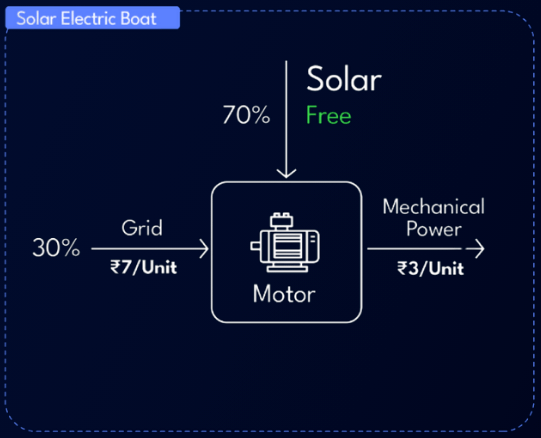

The third and most powerful lever for reducing OPEX is solar energy. For large ferry boats operating at low speeds, solar can contribute up to 70% of daily energy demand.

This further reduces the effective cost of mechanical power from ₹10 per kWh to approximately ₹3 per kWh, once again cutting costs to about one-third.[3]

When these three steps—design optimisation, electrification, and solar integration—are combined, the overall propulsion-related OPEX can drop to nearly one-thirtieth of that of a comparable diesel boat.

The result is a solar-electric boat with dramatically lower operating costs.

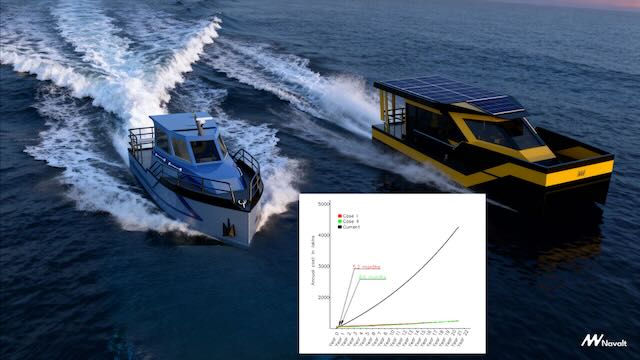

Better Is Clear. But Is It Cheaper?

While solar-electric boats are clearly superior in terms of comfort, emissions, and operating cost, the real question operators ask is: Are they cheaper?

To answer this, we must look at Total Cost of Ownership (TCO):

TCO = CAPEX + OPEX

In a diesel boat, CAPEX consists of the boat, engine with shafting system, and fuel tank. In an electric boat, the engine is replaced by a motor, the fuel tank by a battery, and fuel by electricity. OPEX for diesel boats is dominated by fuel and others include lubricants, filters, frequent maintenance, overhauls, and spare parts. For electric boats, OPEX includes electricity cost, routine maintenance, and dominated by eventually battery replacement.

An electric boat is not a radical departure from a diesel boat; it is a direct substitution of systems. The engine is replaced by a motor, diesel fuel by electricity, and the fuel tank by a battery—while the boat continues to perform the same function.

Speed, Range, and Energy: Why Speed Matters More Than Range

Most boats exist to either move people/goods or perform a work. For passenger ferries with a fixed capacity, the two variables that matter most are speed and range.

Increasing range primarily affects energy storage. A diesel boat needs a larger fuel tank; an electric boat needs a larger battery. Increasing speed, however, affects both energy storage and power. More power means bigger engines and motors.

A 75-passenger ferry illustrates this clearly:

- At 6 knots and 75 km range, the boat requires about 16 kW of power and 108 kWh of energy.

- Keeping the same speed and doubling the range to 150 km doubles energy demand to 216 kWh, but power remains unchanged.

- Doubling speed to 12 knots at 75 km range increases power demand to 200 kW—over 12 times higher—and energy demand to 675 kWh, over six times higher.

- Doubling both speed and range further increases energy to 1,350 kWh, while power remains at 200 kW.

| 6 knots | 12 knots | |

| 75 km | 16 kW power 108 kWh energy | 200 kW power 675 kWh energy |

| 150 km | 16 kW power 216 kWh energy | 200 kW power 1350 kWh energy |

The key insight is simple but critical:

Doubling range doubles energy.

Doubling speed multiplies power over twelve times and energy six times over.

This has profound implications for electric boat feasibility.

Categorising Ferry Applications

Ferry boats can broadly be classified into three categories:

- Low speed (<8 knots), low range (<75 km)

- Medium speed (8–15 knots), medium range (75–150 km)

- High speed (>15 knots), high range (>150 km)

Low Speed, Low Range: A Proven Model

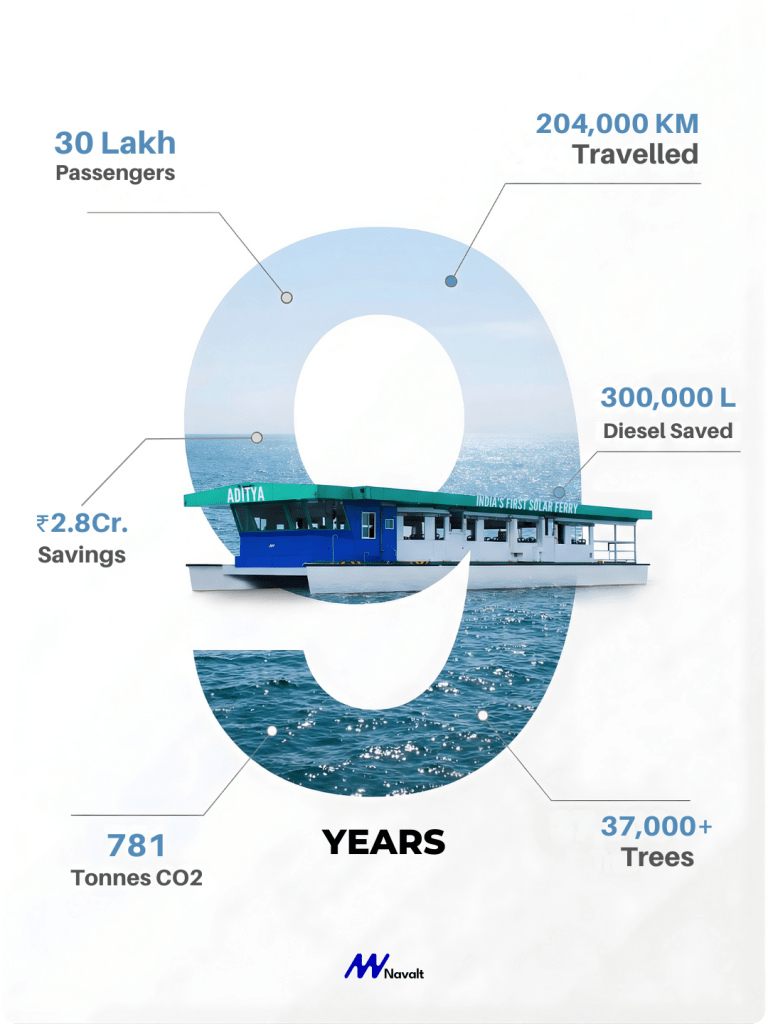

This category is already well established in India. Aditya, India’s first solar ferry, has been operating successfully for over nine years, transporting more than 30 lakh passengers over 204,000 km without consuming a single drop of diesel. It has saved over 300,000 litres of fuel, approximately ₹2.8 crore, and avoided 781 tonnes of CO₂ emissions.

Economically, the model is compelling. A comparable diesel ferry costs about ₹2 crore, while the solar-electric version costs around ₹3 crore. With annual fuel savings of about 35,000 litres (₹35 lakh), the additional CAPEX is recovered in under three years.

Unfortunately, poor technology choices have been made even in this category. For example, boats operating under 8 knots with daily ranges below 65 km—such as Kochi Metro boats each at 7.6 crore—could have been built with LFP batteries at significantly lower cost. Instead, higher-cost configurations have been adopted, leading to unnecessarily high CAPEX. This is the same in the case of West Bengal Electric ferries where the prices is at 17 crore per boat (150 passenger capacity).

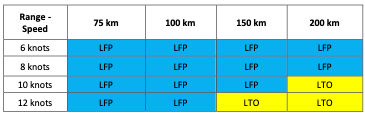

Medium Speed, Medium Range: Technology Choices Matter

Source: [4]

In the medium-speed, medium-range segment, battery chemistry selection is critical. At speeds closer to 8 knots and ranges around 75 km, LFP batteries are economical. As speed and range approach the upper end of the category, LTO batteries become advantageous due to faster charging and higher cycle life.

However, LFP battery prices are falling faster than LTO prices, and charging performance continues to improve. This means LFP will remain viable for an increasing share of this segment over time.

High Speed, High Range: Rethinking the Boat Itself

At speeds above 15 knots, conventional displacement electric boats become impractical due to excessive battery size. The way forward is foiling hulls, which can reduce power and energy requirements by more than 60%.

In this segment, LFP batteries combined with battery swapping or fuel cells are potential solutions. However, fuel cells currently suffer from high CAPEX and OPEX, limiting near-term adoption.

Beyond Ferries: Other Key Opportunities

Tourism Boats: A Natural Fit for Solar-Electric

When we move from public transport to tourism, the operating profile becomes even more favourable for electrification. Tourism boats typically operate at low speeds of 5–7 knots and cover less than 75 km in a day. Operations are usually daytime, with predictable routes and long idle periods between trips—conditions that align perfectly with solar-electric propulsion.

At these speeds and ranges, boats equipped with LFP batteries combined with onboard solar are not only technically feasible but also economically attractive. The quiet operation, absence of vibration, and elimination of fuel smell significantly enhance passenger experience, which is especially important in backwaters, lakes, wildlife zones, and heritage destinations. In this segment, solar-electric boats are often the default optimal choice, not a premium alternative.

Small Fishing Boats: Electrification as a Livelihood Enabler

The fishing sector presents a nuanced opportunity. Large trawlers and high-power vessels that remain at sea for a week or more are currently not suitable for electrification due to energy storage limitations. However, small fishing boats, typically around 10 metres in length, operating on daily fishing cycles, represent a strong and economically viable use case.

These boats usually travel within a 30 km range and carry less than 500 kg of fish. Navalt has built and tested five such solar-electric fishing boats to evaluate real-world performance and economics. A traditional petrol-powered boat in this category costs about ₹5 lakh, while annual fuel and maintenance expenses are around ₹4 lakh.

If a solar-electric fishing boat can be priced between ₹15–20 lakh, the breakeven period falls below five years, even without accounting for fuel price volatility. The economics improve further if existing subsidies for petrol outboard motors and fuel are redirected as CAPEX support for solar boats. With approximately 2.5 lakh such boats operating in India, this segment represents both a large market and a meaningful opportunity to reduce fuel dependence for fishing communities.

RoRo Vessels: Electrifying Vehicle Ferries

Beyond passenger ferries, RoRo (Roll-on/Roll-off) vessels that carry two-wheelers, cars, and trucks are another promising application for electric propulsion. These vessels typically operate on short crossings with high reliability requirements and frequent trips.

RoRo vessels can be effectively electrified, with battery chemistry selection depending on operational patterns. For longer routes with fewer trips per day, LFP batteries are more economical. For short routes with high trip frequency, LTO batteries offer advantages due to faster charging and higher cycle life.

Navalt is currently building two such solar-electric RoRo vessels, each with a 100-tonne carrying capacity, demonstrating the scalability of electric propulsion beyond passenger-only applications. These will operate in Kochi port waters by end of 2026.

High-Speed Patrol Vessels: A Compelling Case for Hybridisation

High-speed patrol vessels present one of the most attractive cases for hybrid propulsion. These vessels typically operate in two distinct modes: a slow-speed patrol mode at 6–8 knots and a high-speed chase mode reaching 40–45 knots.

Conventional patrol boats, usually 10–15 metres long, are equipped with twin high-power engines and water jets rated at 500–1,000 kW each. While this configuration is optimised for high-speed operation, it is extremely inefficient during low-speed patrol. At low engine loads, specific fuel consumption is high, and water jets operate far from their optimal efficiency range. As a result, the mechanical load on the engines can be two to three times higher than what would be required with a system optimised for low-speed operation.

A parallel hybrid system, designed specifically for patrol mode, allows the vessel to operate in zero-emission electric mode during routine patrols while retaining full diesel power for high-speed pursuits. This operational split leads to dramatic fuel savings and can result in an exceptionally short breakeven period—often close to one year.

Emerging Applications: Amphibious and Autonomous Vessels

Amphibious vessels and autonomous surface vessels represent emerging applications where electric propulsion offers clear advantages, particularly for short-range operations. These platforms benefit from precise control, low noise, and simplified mechanical systems—areas where electric drives naturally outperform conventional engines.

As autonomy and specialised waterborne platforms evolve, electric propulsion is likely to become the default architecture, especially in constrained or environmentally sensitive operating zones.

Green Tugs: Policy-Led Transition

Green harbour tugs represent an emerging but strategically important application for electric propulsion. Through initiatives such as the Green Tug Transition Program, policy now mandates ports to transition their tug fleets to electric or hybrid propulsion within a defined timeframe. This regulatory push is crucial, because with current technology and pricing, the standalone economic viability of electric tugs can be challenging.

Tugs are high-power vessels, but their operating profile often involves short bursts of intense activity, followed by idle periods. Electric or hybrid solutions become viable when operating durations are limited—typically around two hours per duty cycle—and the vessels are used repeatedly throughout the day. In such cases, frequent charging and predictable schedules can offset high upfront costs. With the policy mandates, adoption will take off; green tugs can become a cornerstone of decarbonising port operations.

Inland Cargo Vessels: Scaling Zero-Emission Transport

Another promising application lies in inland cargo vessels with capacities of around 1,000 tonnes, carrying both liquid and bulk cargo. These vessels operate on fixed routes along national waterways, making them well suited for electrification.

A practical approach for this segment is the use of containerised battery systems, which can be swapped approximately every 200 km. Combined with modest onboard support from wind and solar, this enables vessels to operate as zero-emission ships along entire stretches of National Waterways 1 and 2. The containerised format also decouples the battery asset from the vessel, opening new business models around energy-as-a-service and infrastructure-led deployment.

The Long-Term Vision: Green Coastal and Sea-Going Ships

The ultimate objective of marine electrification is the development of green ships for coastal and ocean-going cargo transport. While technically possible in limited forms today, the economics and energy density required for long-range sea-going vessels are still evolving. For this segment, both technology maturity and cost competitiveness are likely a decade away.

However, progress in batteries, hybrid systems, fuel cells, wind assistance, and vessel efficiency is cumulative. Each successful inland and nearshore application builds the foundation for future ocean-going solutions.

Moving Step by Step Towards Electrified Oceans

Navalt’s journey reflects this phased approach. Today, 40 solar-electric boats are in operation, with 39 more under construction. These vessels operate across eleven states in India and have also been exported to Canada, Israel, the Maldives, and Seychelles.

Each project adds operational data, improves design choices, and strengthens the ecosystem required for scale. Together, these steps move us closer to a future where waterways are cleaner, operations are quieter, and oceans are progressively electrified—not through leaps of faith, but through economically sound, technically proven transitions.

References

[1] – Solar electric Boats book

[3] – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379047865_Cost_of_energy_in_a_vessel paper

[4] – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373482101_Technological_choices_of_a_medium_speed_electric_ferry paper

Thanks Sandith, this is very insightful!

LikeLike